People have used cobalt for many things. It has a long history as a pigment; it’s been used to decorate porcelain for centuries in China, and cobalt blue was a favorite paint color for impressionists such as Renoir and Monet. It’s found in many high-strength metal alloys. It’s necessary for human life, found in vitamin B12.

In recent decades, cobalt has become part of the standard formulation for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Batteries in most smartphones and other consumer electronics use a formulation that calls for a majority cobalt oxide cathode (LCO). Cathodes used in electric vehicles generally use different formulations such as nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA), where cobalt makes up roughly 15% of active material, and nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC), where cobalt can be up to 33% of active material.

As the need for high-energy batteries increases, more cobalt is being extracted from the soil, which is troubling for a number of reasons. And while cobalt is valuable to recyclers, there currently aren’t enough of them to process all of the emerging waste batteries on a global scale.

Cobalt is toxic when inhaled or consumed at above-average levels, which is generally between 5 and 40 micrograms per day for humans. Cobalt toxicity can lead to chronic health problems including asthma, decreased lung function, enlargement of the heart, and congestion of the liver and kidneys. It may even affect the reproductive system in both men and women. While people who mine and process cobalt are at the most acute risk for problems, as more lithium-ion batteries find their way into waste streams and water supplies, the risk to the general public increases as well.

Much of the world’s cobalt—up to 70% by some estimates—comes from central African nations such as Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo that lack proper safeguards for personal health and the environment. Many small “artisanal” miners are known to take advantage of forced child labor, with up to 40,000 children as young as six years old mining cobalt in the Congo. The mines themselves are often unsafe, suffering from poor ventilation and prone to collapse. Human rights organizations have begun to focus on the cobalt trade in Africa, and cobalt mining has created ongoing environmental damage in countries including Cuba and Australia.

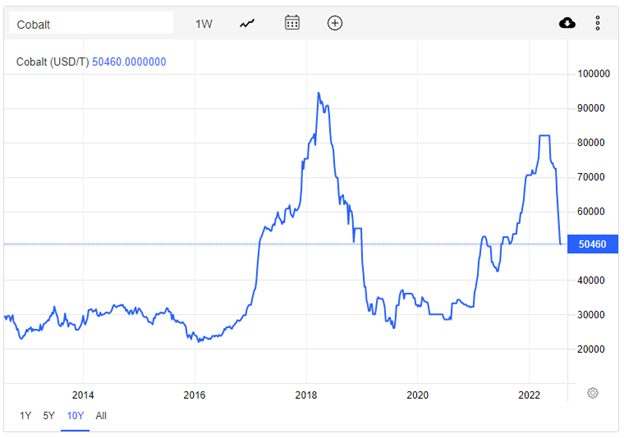

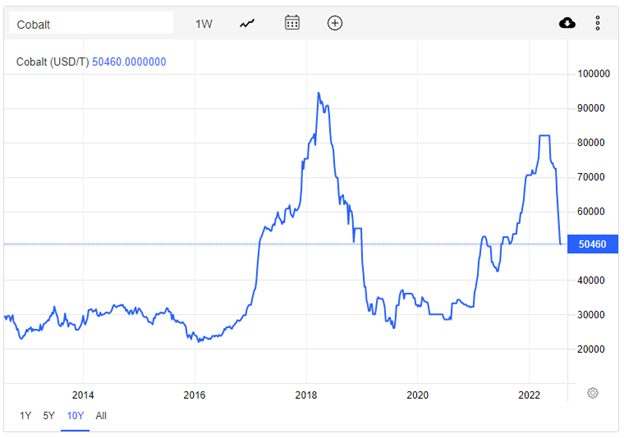

On a more practical level, cobalt pricing has been volatile over the past few years. Prices have swung from roughly $22,000 USD per metric ton in 2016 to a high of $95,000 in 2018, only to fall back to $26,000 in 2019 before surging to $82,000 in 2022. Sudden spikes make planning difficult for battery manufacturers, and price increases are often passed along to end consumers; one only has to look at recent prices for EVs, which have gone up rapidly rather than decline as forecasts had predicted.

Chart via Trading Economics

Some battery companies do seem to be taking notice. Many battery energy storage systems (BESS) are now leveraging lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries, which contain no cobalt. BESS with LFP batteries sacrifice the energy density of higher-end models with NCA/NMC batteries, but consumers seem to be OK trading reduced energy for lower cost. LFP still have many of the flammability and toxicity issues common to all lithium batteries, but the move away from cobalt is at least a step in the right direction.

The next step for the battery industry should be a move toward chemistries that are inherently non-toxic AND non-flammable. Fortunately, there are a number of companies (including Alsym Energy) working toward that goal with technologies including sodium-ion, nickel-zinc, and more that are safer for people and safer for the environment. Together, we can help ensure the planet goes green and not cobalt blue.