Utilities and developers across the globe are deploying gigawatts of battery energy storage systems (BESS) to buffer an increasingly unstable grid from rising electricity demand and adoption of intermittent renewable energy.

Of these batteries being deployed, 98% rely on lithium-ion—a chemistry that offers high energy density but introduces explosion and fire risk under specific failure conditions. To combat its volatility, the industry has responded with a string of new engineering controls such as thermal management and fire suppression infrastructure, which add cost and complexity to projects. Despite these controls, large-scale fire incidents are still happening.

We’re at a critical juncture in our energy storage future where we must ask ourselves some hard questions. As we scale up, the critical issue won’t be how many sensors to install or how to make more sophisticated battery management systems. It will more fundamentally be whether you can engineer a truly safe system around a chemistry with the capacity to combust.

Blaming the Pin, Ignoring the Grenade

Battery manufacturers often argue that unprovoked combustion of lithium-ion cells is extremely rare. The data backs that up; these events occur at a rate of roughly 1 in 10–40 million cells. Instead, research has exposed that most major battery fires start with “balance of plant” (BOP) components—inverter faults, coolant pump seizures, or Battery Management System (BMS) errors.

Looking at the bigger picture, incidents that start with something relatively mundane (a coolant leak) but escalate into multi-day emergencies reveal something more concerning. Recent incidents show the deeper pattern:

- Warwick, NY (June 2023 and again in December 2025): In two very similar events happening two years apart, moisture infiltrated a Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) facility during a rainstorm, causing electrical shorts. Both fires burned for multiple days as fire crews were forced to wait for the chemical reactions to deescalate on their own.

- Moss Landing, CA (Sep. 2022): Rainwater entered through a dislodged umbrella valve at the Elkhorn battery facility, causing electrical arcing. Thermal runaway occurred in one BESS unit, requiring emergency response and temporary facility shutdown.

- Victoria, Australia (July 2021): A cooling system leak during commissioning caused a short circuit in an electronic component. The resulting thermal runaway spread to an adjacent compartment, consuming two Tesla Megapacks.

Yes, these were failures that started with something else other than the battery. But attributing the damage from a massive thermal event to a BOP component is like saying a grenade explosion was caused by a pin malfunction, not the explosive inside.

In these cases, the precipitating events were equipment malfunctions that occur routinely in any industrial system at some point during its 20-plus year system life.

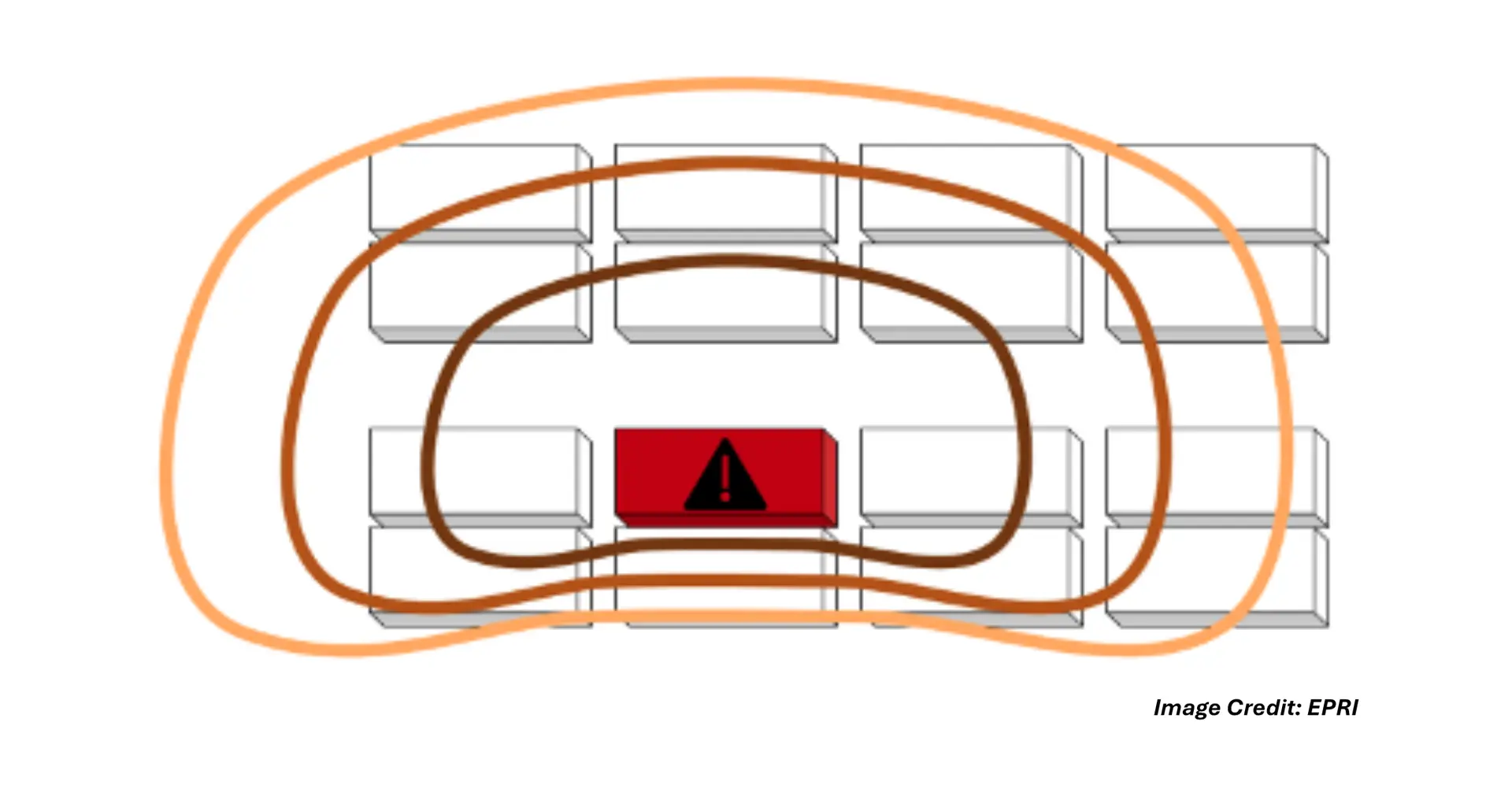

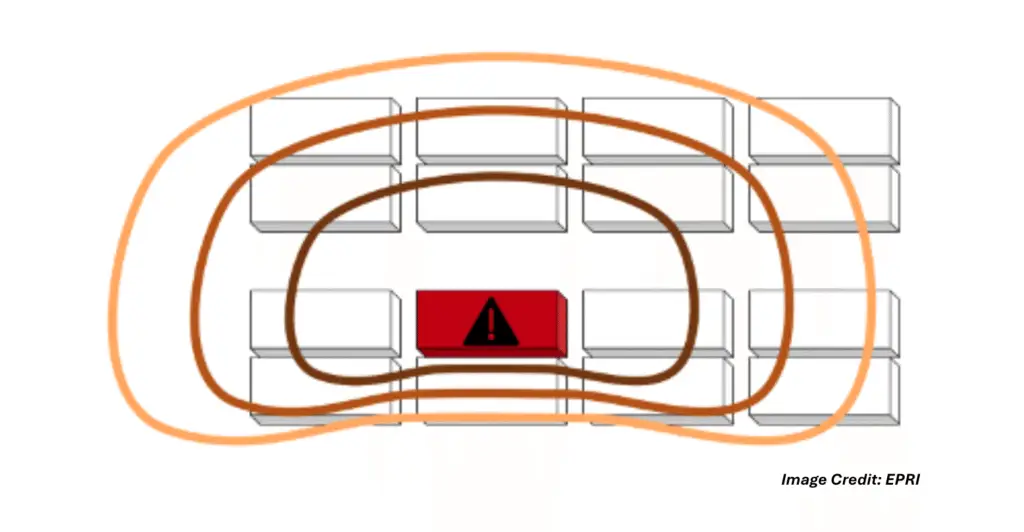

What transformed them into prolonged disasters was the combustibility of the lithium-ion chemistry and its failure pathway to thermal runaway. During thermal runaway, the cathode releases oxygen that fuels a self-sustaining reaction with the flammable electrolyte. Water can cool the battery’s exterior but cannot stop the internal chemical reaction, requiring massive volumes and sustained, multi-day application to prevent spread.

LFP – Not a Silver Bullet

The ESS industry is currently transitioning from high-nickel Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC) to Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) because LFP has a higher ignition threshold – meaning it takes more heat to start irreversible chemical reactions.

But as we saw twice in Warwick, New York, LFP is not a silver bullet, nor will it ever be.

When moisture infiltration caused electrical shorts, the LFP-based facilities burned for days. While LFP may require greater thermal input to ignite, its post-ignition behavior mirrors other lithium-ion variants: an inability to suppress directly, the release of toxic off-gases, and extended duration fires.

Intrinsic Safety Through Chemistry

Effective risk mitigation requires shifting from a responsive strategy (i.e. adding more sensors and alarms) to intrinsic safety through chemistry replacement. This is where advanced sodium-ion chemistries, particularly those based on polyanionic sodium iron pyrophosphate (NFPP), represent a categorical departure from the status quo.

Advanced NFPP sodium-ion, including NFPP+:

- Decouple Heat from Reaction: Lithium-ion thermal runaway releases oxygen from the cathode, fueling the fire internally. Advanced NFPP breaks this loop. Without oxygen generation, BOP failures cause a system shutdown rather than cascading combustion.

- Use Non-Flammable Electrolytes: Testing demonstrates that these cells do not exhibit thermal runaway even under nail penetration or external heating.

- Are Safe to Transport: Unlike lithium-ion batteries, which must retain a >30% charge during transport, sodium-ion variants can be discharged to zero volts, allowing them to be shipped as electrically inert equipment.

Prioritizing Failure Resilience

Lithium-ion cells rarely fail, but cooling systems and sensors inevitably will over a 20-year lifespan. The distinction for fire protection professionals is not between monitoring technologies—it’s between electrochemistries that combust when these systems fail versus those that don’t.

By adopting advanced chemistries like NFPP+, the industry can move toward a standard where coolant leaks remain simple maintenance issues, rather than multi-agency emergencies. Thermal events may not originate with battery chemistry, but they can certainly end with them. It’s time to change the common denominator.